It’s notoriously difficult to direct cancer drugs to only the cells you want to target—they often kill many healthy cells in the process, making the patient feel sicker, or the body attacks them assuming that they are invaders. For the past few years, researchers have been devising new ways to disguise drug molecules so that they will reach cancerous cells more efficiently. Now a team of researchers from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill may have found the best cloaking mechanism yet, masking drugs as blood cells, according to a study published yesterday in the journal Advanced Materials.

Platelets, a type of blood cell, are a good disguise for drugs because blood cells naturally stick to cancer cells, so the drugs can go directly to tumors or destroy cancer cells in the blood stream before they colonize new organs. Plus, since the platelets are derived from the patient’s own body, the immune system doesn’t immediately try to destroy them, allowing the drugs to stay in the system for longer, the study authors tell Science Beta.

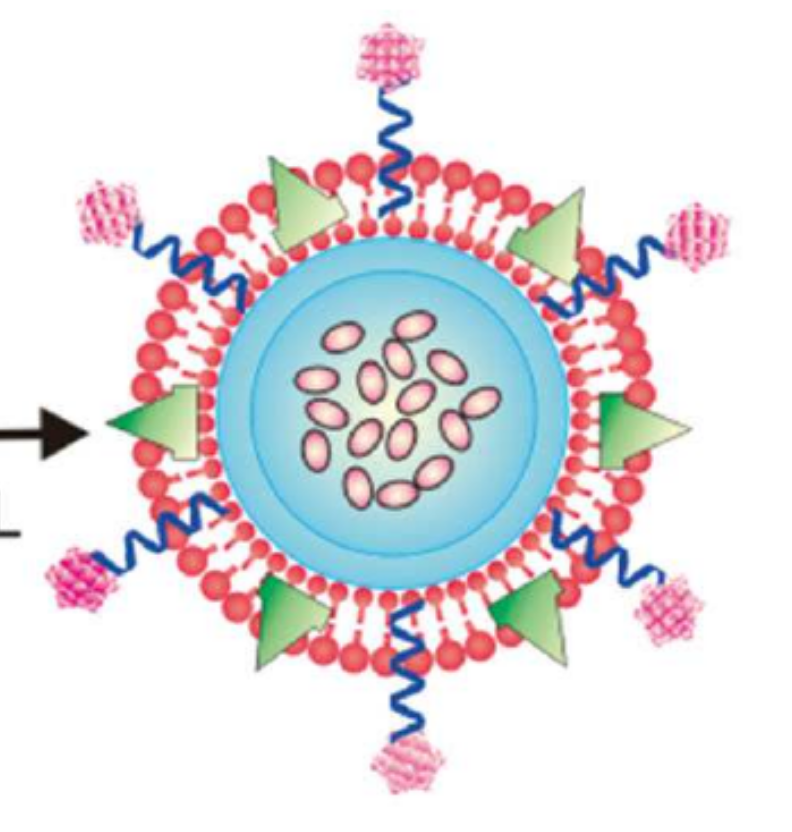

A schematic of the cancer-fighting drug coated in platelet membrane

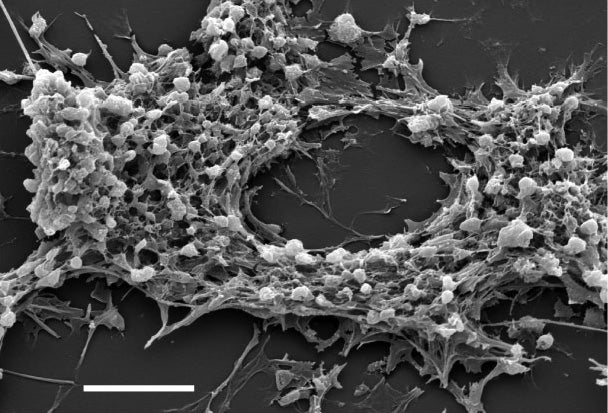

In this study, the researchers tested their method on 231 mice with tumors. They first separated the platelets from the blood drawn from each mouse, then removed the platelet membranes and combined them with two cancer-fighting drugs. The result was a sphere with a drug on the inside, surrounded by the platelet membrane. The researchers then injected the spheres into the mice’s bloodstream. They found that the particles stayed in the bloodstream for 30 hours, 24 hours longer than the particles not coated with platelet membranes, and that the coated molecules killed cancer cells and stopped tumor growth much more effectively.

Since this is a study in mice, this technology isn’t yet ready to be used in humans. And while it makes sense that blood cells would be a good disguise for drugs because of blood’s relationship with tumor cells, it’s unclear if the platelet membranes work better than similar efforts to camouflage drugs as innocuous viruses or bacteria. The researchers plan to answer some of these questions in future studies. They also anticipate that this method could be used to send other types of drugs to targeted places in the body to heal leaky veins or combat conditions like heart disease.