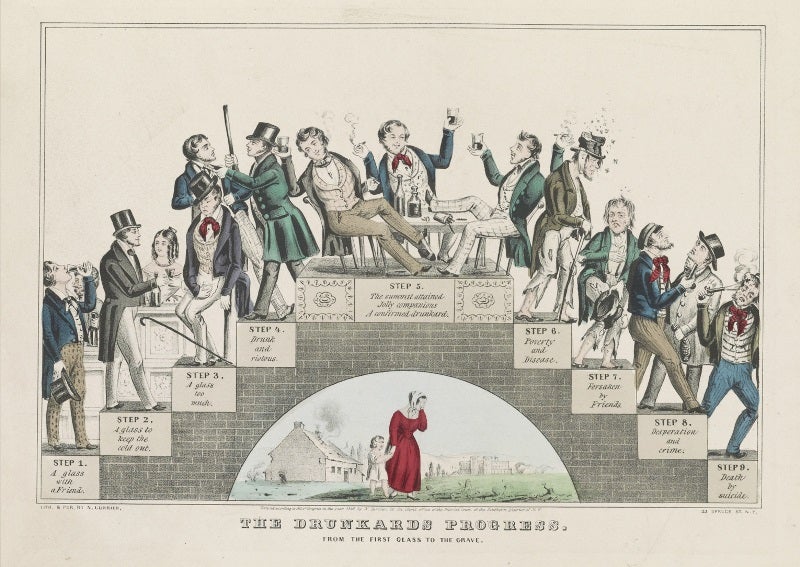

Alcohol consumption has been a part of human activity for millennia though not everyone does so responsibly. Back in the 1800s, public health officials first took note of the issue of alcohol abuse, which was known then as intemperance. They were keenly aware there was a link between the amount of the fermented byproduct consumed and both short and long term effects on personal health. Yet, while the social and psychological impacts were apparent, the actual consequences at the physiological level would require time.

Over the last 150 years, the medical problems associated with alcohol have been elucidated with more than enough concrete evidence to support them. The major diseases include cardiovascular disorders, loss of bone mass, onset of cancer and the most common of all, liver disease. The compiled data also suggest the major contributing factor is not the alcohol itself, but the inflammation caused by its ingestion. The immune system is negatively affected, leading to the propensity for more frequent dysregulation.

Whenever inflammation is suspected as a cause of long-term medical consequences, the microbiome must be taken into consideration. However, until recently, little has been done to find any links between the nature of the microbiota and the onset and/or progression of disease. One of the few meaningful studies to show any links was published in 2012 when an American team of researchers found chronic alcohol consumption led to changes in the nature of the bacteria in the colon. Yet how this change happened and how it impacted health was left unanswered.

However, in the last few weeks, two important papers have been published to highlight how bacteria contribute to the overall effects of alcoholism. The first deals with the interactions between the host and the microbiome during alcoholic liver disease. The other reveals the effects on the microbiome and body as a result of only one binge drinking event.

Alcohol liver disease (ALD) is the most common liver-related medical problem and has been intensively studied to both understand as well as help to resolve the condition. Unfortunately, there are few answers. What has been known is the understanding of the gut-liver axis, in which changes in the gastrointestinal system contribute directly to functions in the liver. With this information at hand, a duo from the University of California took a closer look at how the gut-liver axis may involve the microbiome. What they found highlighted the scope of the problem and the reasons for its intransience.

Instead of only one specific link, they found many. The first confirmed the earlier observations of a change in the microbiome. As alcoholism progressed, the gut underwent a form of dysbiosis. The levels of good bacteria, such as the probiotic Lactobacillus, dropped while those of potential pathogens rose. They also highlighted an overgrowth of these bad bacteria leading to an increase in toxins and other liver-damaging chemicals. Inflammation would subsequently occur, leading to increased permeability of the gut. At this point, those damaging byproducts would be easily translocated to the blood serum and the liver. Over time, the damage would become unstoppable and eventually, disease would occur.

The long-term effects revealed the importance of the microbiome in alcohol disease and the need for moderation in consumption over time. Yet, the data offered little to demonstrate the immediate effects of a binge night. That, however, was unveiled by a team from the University of Massachusetts Medical School, who found that even one abusive night of drinking could have significant health consequences much worse than a hangover.

The team asked a group of 11 males and 14 females, none of whom had any history of alcohol abuse, to drink enough alcohol to qualify for a binge drinking session. For the next 4 hours, at 30 minute intervals, and at 24 hours after consumption, blood was drawn and tested for levels of toxins, immunological activity and bacteria activity. As expected, all levels were raised significantly over the first few hours, suggesting a process of bacterial overgrowth and subsequent inflammation was occurring.

Based on the results, the short term effects appeared to mimic the long-term ones. With a single drinking event, the bacteria were activated – presumably through alcohol-related environmental stress – leading to an increase in toxin production. Inflammation was then triggered, leading to permeability and translocation of the toxins into the blood. The overall effect on the body would lead to decreased feeling of wellness due to inflammation as well as other behavioral problems including fatigue, mood changes, cognitive dysfunction and disturbances in sleep rhythm.

While the studies reveal the detrimental consequences of both binge drinking as well as overall long term abuse, neither focused on the effects of moderate drinking. In contrast, other studies have highlighted benefits from the occasional bottle of beer, glass of wine or shot of liquor. Ironically, the mechanism behind this positive result is manifested through the reduction of inflammation.

The dichotomy of the research reveals the double-edged sword that is alcohol. When used properly, it may be good for you yet when abused; it can lead to immediate as well as lasting problems. In terms of the best way to move forward, especially with the Memorial weekend approaching, the best way forward can be best summarized as follow: you can have a good time with some alcohol but if you end up running a tear, it might cost you and your microbiome dearly.