Summer sea ice in the Arctic got a respite this year, as did the Greenland ice sheet, because cooler summer temperatures prevented a repeat of 2012’s record-setting melt. But the past seven summers have seen the lowest amounts of Arctic sea ice since satellite records began in 1979.

These and other environmental conditions in the Arctic are detailed in the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration’s (NOAA) annual “Arctic Report Card,” which the agency released Thursday at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco.

“What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic.”

Overall, it’s been “another year in the new normal,” said Army Corps of Engineers geophysicist Don Perovich, a contributor to the report. Scientists like Perovich are struggling to figure out what the new baselines are, as warming transforms the region. By September, when the 2013 summer melt ended, Arctic sea ice coverage was at its sixth lowest extent since 1979. During the summer, melting took place on about 44 percent of the surface of the Greenland ice sheet—smaller than 2013 historic 97 percent, although not particularly low compared to the long-term record.

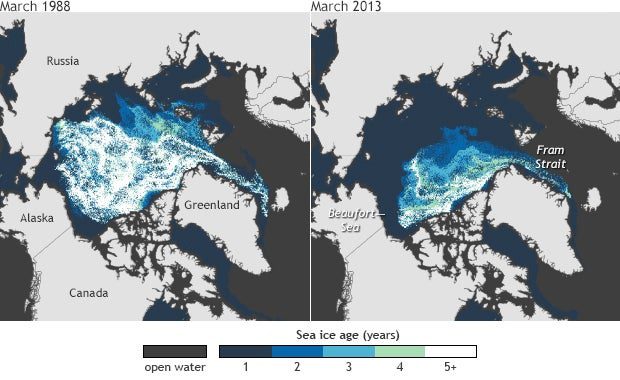

In March 2013, multi-year thick sea ice made up just 7 percent of the Arctic ice cap, and first-year ice comprised about 78 percent, compared to 26 percent and 58 percent respectively in March 1988. “Younger” sea ice does not reflect as much solar radiation back into the atmosphere, intensifying warming trends caused by human-propelled climate change.

Temperatures split into unusual warm and cool extremes over different Arctic regions during the spring and summer. Just below the Arctic Circle, Fairbanks, Alaska, had 36 days at or warmer than 80 degrees F, a new record, while Central Alaska had its coldest April since 1924. May snow cover in Eurasia was at a historic low this year, with temperatures about 7 degrees F. higher than in the past. Spring and early summer snow cover across the North American Arctic was the fourth lowest on record.

As plant life increases and the climate becomes drier, wildfires burn more frequently.

Arctic land is “greening,” as warmer temperatures have gradually extended the growing season by nine days for each decade since record-keeping started in 1982. But as plant life increases and the climate becomes warmer and drier, wildfires are burning more frequently. More study is needed to figure out how these fires may affect the amount of soot, or “black carbon,” in the Arctic. Black carbon, created by the incomplete burning of fossil fuels or biomass, absorbs solar radiation. In the atmosphere, black carbon can increase temperatures; landing on snow or ice, it can accelerate melting. Levels of black carbon being carried to the Arctic by global winds have roughly halved since the early 1990s, when the economic contraction of the former Soviet Union cut industrial activity.

Migratory Arctic tundra caribou and reindeer herds have diminished over the past several years, according to the report. While smaller winter ranges may play a part, the decreases may also involve natural populations shifts, according to Michael Svoboda, of the Circumpolar Biodiversity Monitoring Program. If so, both species may bounce back in coming years despite the changing environment.

Growing numbers of musk oxen, meanwhile, are largely thanks to active conservation and re-introduction programs, Svoboda said.

Current status of 24 major migratory tundra reindeer and caribou herds

Long-term warming continues to push Atlantic cod, capelin, salmon, and other fish species northward. The report recommends that scientists start monitoring and assessing fish populations in deeper waters further north, to figure out whether and how they are adapting to climate change. This year’s report card did not include data on polar bears or other marine mammals.

Government funding shortfalls are forcing reductions in Arctic monitoring systems.

There is growing evidence that the Arctic’s new normal is driving changing weather patterns in lower hemispheres. “The Arctic is not like Vegas,” said University of Virginia ecologist Howie Epstein, another report contributor. “What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic.” Scientists still don’t fully understand how these systems interact, however, highlighting how much about the region is still a mystery.

Parting a bit from the straight science, the researchers presenting the report card went out of their way to mention that government funding shortfalls are forcing reductions in Arctic monitoring systems. “We need to be better prepared for the increasing level of activity in the Arctic,” said Martin Jeffries of the University of Alaska Fairbanks, a science adviser for U.S. Arctic Research Commission. “If we can’t see what’s going on, we can’t be prepared” for what the new level of human activity in the warming Arctic will bring, from rescues to oil spills.

The Arctic is a “data-sparse region, just as we need to better understand and model that system,” said Perovich, “to predict what will happen in the future.”