About an hour ago, the Associated Press’s official Twitter account, @AP, issued this tweet (it’s since been removed):

Hacked @AP Tweet

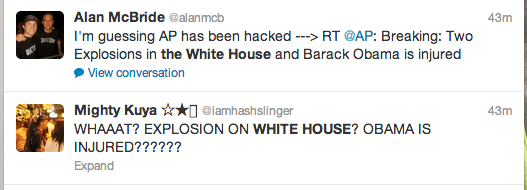

I was in the bathroom reading Twitter (I know.) when this first broke, and the first thing I saw wasn’t one of the most respected news sources in the world tweeting that the White House had been bombed. I don’t follow the AP on my personal account, so the first thing I saw was this:

The next three tweets I saw about this possibly breaking news story were as follows: “there’s no way that @AP tweet is real,” “Not believing this,” and “h a c k t i m e.” Not a single person in my feed believed the tweet; the closest was Anil Dash asking for “other sources.” The jokes followed immediately–jokes about those who had bungled coverage of the Boston Bombing (the New York Post, CNN, former Reuters social media editor Matthew Keys, Reddit), and then aggressive ignoring of the tweet. My feed, largely made up of reporters, editors, writers, and other news-types, barely even bothered to make a reasoned rejection, so silly was the AP tweet and so jaded our reaction to news.

That’s the same experience everyone had; within seconds, the balance of those talking about the tweet swung from earnest disbelief to cries of “hacked,” “fake,” and scorn. By five minutes in–an eternity on Twitter!–the conversation was almost entirely about the “AP hack,” not the “news.” Even the stock market, run by alarmist algorithms, snapped back from an absurd drop in minutes.

The Syrian Electronic Army, a largely unknown group which claimed credit for the hack, has been busy the past few days, taking control of the Twitter accounts of NPR, the BBC, @60Minutes, and more. But they’re small-h hackers, nominally political and apparently accomplished at getting access but less concerned with causing real damage than in pranks and delighting in their own cleverness. When they took control of @FIFAWorldCup, they tweeted a few times about a conspiracy against the Syrian national soccer team and then a whole bunch more times saying things like “Twitter #failure” and “Syrian Electronic Army was here.” None of their work suggests that this is a serious political group trying to effect change or even mere chaos; this is probably a handful of dumb teens.

The AP tweet was not hard to pick out as a hoax. The phrasing was wrong; the AP writes “BREAKING” in loud capital letters, whereas the hacked tweet was properly capitalized; it was sent via the web whereas legitimate @AP tweets are usually sent via Social Flow, a marketing service; and the president was referred to simply as Barack Obama, a violation of the AP’s style guide. That’s on top of the fact that, well, if there was a bombing at the White House, it’s pretty doubtful that @AP, fast as they are, would be the first and only source to get the word out; they weren’t nearly the first to tweet about the Boston Bombings, for example, and this hacked tweet was not accompanied by any corroborating eyewitness reports.

Compare the effect of this fake tweet–near-instantaneous dismissal and eye-rolling–with the very worrying case of Sunil Tripathi, a Brown University student who had been missing for a few weeks. At 2:43AM early in the morning of April 19th, one Greg Hughes, an active Reddit contributor, tweeted Tripathi’s name as a possible suspect in the Boston Bombing, citing a mention on the Boston Police Department’s scanner feed. The Atlantic’s Alexis Madrigal was unable to find anything resembling Tripathi’s name in the scanner’s logs, but it didn’t matter; within hours, Sunil had become the number one suspect in the bombings for Twitter and Reddit.

He was cleared by late afternoon, when the FBI identified the Tsarnaev brothers as the primary suspects. His whereabouts are still unknown.

Hughes’s tweet was earnest; it cited a source assumed to be trustworthy (though it is not, and it doesn’t seem to have come from that source anyway), it came from someone trying to help. It was plausible. The easiest way to fool someone is to have already fooled yourself, and in publishing something he thought was true, Hughes’s tweet became far more powerful than anything a prankster group of Syrian hackers could come up with.

* * *

These two stories show both sides of the crowd-sourced hive mind with which we analyze information on Twitter. On the one hand, the masses came to the right conclusion very quickly in the case of the AP hack; if you looked at literally a single tweet besides the one from @AP, even if you weren’t sure what to think, you’d immediately have to consider the possibility that the tweet was not genuine. It caused no damage, no panic. Nobody was hurt, really; it’s hard to even blame the Associated Press. It could happen to anyone, and the AP was conscientious in conveying what had happened (and getting their Twitter feed temporarily shut down) within minutes. The power of the crowd directed people to the truth.

And yet the painfully earnest computer-chair detective work from Reddit and Twitter may well have destroyed the life of an innocent college kid from suburban Pennsylvania. We don’t know where he is or if he’s okay, we don’t know if he’ll come back or how he’ll recover from being falsely accused of mass murder if he does. When we discuss the problem of oversaturation of news–which we should, repeatedly and at length–we need to remember that. The Syrian Electronic Army’s intentions may have been to hurt, and Reddit’s intentions may have been to help, but it doesn’t matter. Misinformation is misinformation, and Reddit proved a far more effective and destructive source than the hackers.