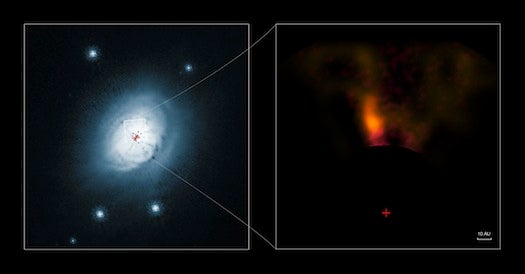

Two views of the gas and dust around star HD 100546

Astronomers have likely caught one of the first glimpses of a planet being born.

Over the past few years, other astronomy teams have found evidence of other still-forming baby planets, but this object may be the youngest yet. “The other planets are a little older,” says Sascha Quanz, an astronomer at ETH Zurich in Switzerland who led the discovery, in a phone interview.

Using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile, Quanz directly observed a planet still in the midst of a disk of gas and dust that surrounds its central star, HD 100546, located 335 light-years away from Earth. The planet hasn’t had the time to gather enough mass to clear the dust around it. The other probable protoplanets, discovered in 2011 and 2012, are a step ahead. “They have already cleared a big gap in the disk of their host stars,” Quanz says.

The newfound object is very bright, which Quanz thinks is because gas is actively falling on the forming planet. Right now, the planet is about as massive as Jupiter, Quanz says. Like Jupiter, it is also gas giant.

Artist’s rendition of the forming gas giant

Quanz will still have to confirm that the data he and his team gathered really point to a forming planet. Another possible explanation for what they’re seeing is that the object is actually being ejected from its solar system, he says. There are data, although not direct observations, that suggest HD 100546 has another planet orbiting closer to it. Interactions between two planets closer to the star could shoot one of the planets out into the dust ring.

Observations made about five years from now should help astronomers differentiate between the two scenarios. Why five years? From its location, astonomers expect the new object to make a full orbit every 360 years. So after five years, the planet should move five degrees, if it’s truly in orbit as forming planet.

Quanz and his team will make some observations far before that, however. In April, they’ll get another turn at the Very Large Telescope, during which they’ll make measurements that will help them determine the object’s temperature. If they’re lucky, Quanz says, they may be able to observe the object accreting gas–growing like any healthy baby would.

Quanz and his team published a paper today about their discovery, in the journal Astrophysical Letters.