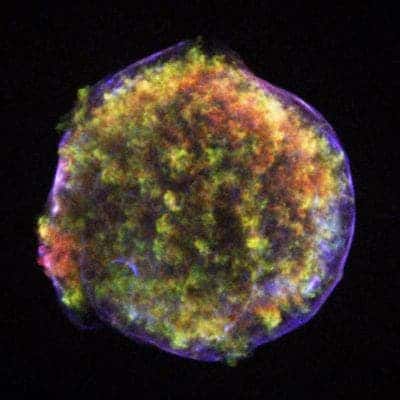

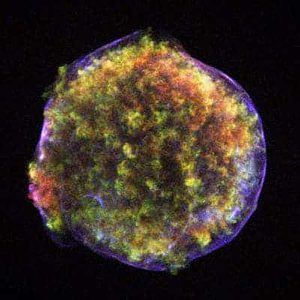

Supernovae are one of the most energetic and brightest events in the cosmos, often so powerful they outshine whole galaxies. They’re considered to play a major role in our understanding of the Universe, which is why scientists have invested so much time and effort into studying them. A recent study of X-ray and ultraviolet observations from NASA’s Swift satellite has helped astronomers understand better how Type Ia supernovae come to be.

A Type Ia supernova forms when a white dwarf, the remnant of a star that has completed its normal life cycle and has ceased nuclear fusion, reaches a critical mass and detonates. This certain supernova family has been found to be extremely useful to astronomers’ studies, who have used their intense brightness as beacons or candle lights to determine vast distances in space. Also, studies of Type Ia supernovae led to the discovery of dark energy, which garnered the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Despite the fact astronomers have known for decades how Type Ia supernovae form, the exact mechanisms that lead to their formation are currently yet obscured.

“For all their importance, it’s a bit embarrassing for astronomers that we don’t know fundamental facts about the environs of these supernovae,” says Stefan Immler, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

“Now, thanks to unprecedented X-ray and ultraviolet data from Swift, we have a clearer picture of what’s required to blow up these stars.”

What sets off a supernova

The main model of formation for a Type Ia supernova involves a close binary star system. There are two dominant theories regarding this. The first and most popular theory currently suggests a white dwarf orbits a normal star and pulls a stream of matter from it, feeding from it until it reaches the necessary mass and explodes into a supernova. A second possible mechanism for triggering a Type Ia supernova is the merger of two white dwarfs, which collide like vast hypermassive billiard balls leading to a cataclysmic blast.

NASA’s Swift satellite, which orbits the Earth and is primarily used to sniff out gamma-ray bursts emitted from far away black holes, is also used from time to time to study supernovae. Its latest find came after it was directed towards the closest Type Ia supernova, called SN 2011fe, offering scientists data that suggest the white dwarf from which it sprang was a particularly picky eater.

“It’s hard to understand how a white dwarf could eat itself to death while showing such good table manners,” said Alicia Soderberg of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA).

Namely, the astronomers couldn’t find any signs or traces left behind from a possible star explosion, the supernova exploded perfectly clean. Additional studies using NASA’s Swift satellite, which examined a large number of more distant Type Ia supernovae, appear to rule out giant stars as companions for the white-dwarf progenitors. When X-ray data was studied, scientists couldn’t find any X-ray point source, indicating that supergiant stars, and even sun-like stars in a later red giant phase, likely aren’t present in the host binaries. Swift’s X-ray Telescope (XRT) has studied more than 200 supernovae to date, of which about 30 percent are Type Ia.

Also, Swift’s Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope (UVOT) looked at 12 Type Ia supernova events within 10 days since their explosion. If the supernova would’ve been triggered by the interaction with larger, brighter stars, then its shock wave should have produced an enhanced ultraviolet light. Nothing of the kind was detected, which combined with other studies findings and X-ray evidence suggests Type Ia supernovae likely originate from a more exotic scenario, possibly the explosive merger of two white dwarfs.

“This is an exciting time in Type Ia supernova research since it brings us closer to solving one of the longest-standing mysteries in the life cycles of stars,” said Raffaella Margutti of the CfA, lead author of the second paper.

The researchers’ findings are set for publishing in April in the journals The Astrophysical Journal Letters and The Astrophysical Journal.