Playgrounds are competing for kids’ time and losing. Nearly 25 percent of children ages 9 through 13 have no free time for physical activity, and a child is six times as likely to play a videogame as to ride a bike. The playgrounds of tomorrow must offer something that even the most enticing virtual offerings cannot: real spaces that look at least as amazing as anything virtual. Architects and design firms are remaking the playground by taking virtualization head on. These spaces are complex and engaging, and some even have buttons to push.

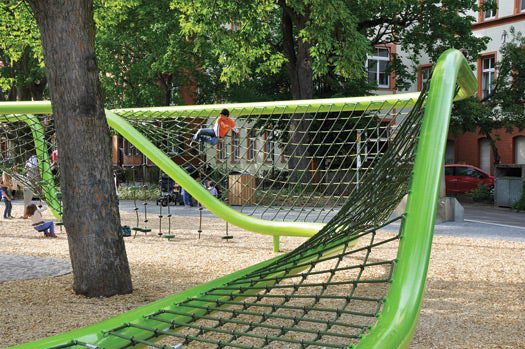

Schulberg: Wiesbaden, Germany

To create an undulating climbing space that meanders through the trees, designers erected two green steel pipes with a net strung between. In some sections, traversing the structure can involve swinging from ropes with rotating plates.

Mobius Climbers

A Möbius strip–like climbing wall made of a textured anodized aluminum sheet, studded with polyester resin (fake rock) handholds, forms a challenging landscape to explore. Therapists use the climbers to help children overcome sensory-processing disorders.

Wall-Holla

What happens to a jungle gym when it’s compressed? It turns into a maze, a fortress, a rock-climbing wall or a soccer goal. Sixty children can comfortably fit in and on Wall-holla, a structure 16 feet tall and 52 feet long.

Wall-Holla 2

Its exceptionally efficient design compresses a colorful 3-D climbing ribbon between two mesh walls, creating a unique experiential environment that, due to its compact size, can fit into even the most limited playground site.

Geometry Playground

In this traveling geometry exhibit and playspace, children roam through walls of torqued cubes, parabolic curves and wavy mirrors; play with stacked forms and glowing building blocks; and climb gyroids and a stellated rhombic dodecahedron. They might even learn some math as they do.

Geometry Playground

In 2010, the Exploratorium science museum in San Francisco debuted its traveling playground, an innovative concept with an innovative goal: to introduce children to the complexities of geometric shapes by letting them physically explore them.

Monstrocity

Climbable tubes made of wrought-iron netting wrap around two aircraft fuselages, a fire engine, a castle turret, three tram cars and a 25-foot-tall cupola in this adjunct to the St. Louis City Museum. Iron “slinkies” narrow and spill out onto a three-story slide. Designed by Bob Cassilly.

Neos

NEOS introduces videogame elements—blinking lights, buttons, beepers and timers—into outdoor playgrounds. Players run, jump, and work together to chase down light as it bounces from panel to panel throughout the rubberized metal structure. The light-tag games are aerobically intense and last just a minute at most.

Snug Kit

Nine objects—mounds, bumps, walls, waves, noodles—form a playground-in-a-box. Children can spin the bumps, fit the waves together to form a slide, and use the walls (which are semicircular) to build tunnels or, flipped, as seesaws.

Snug Kit

The London-based brother and sister team behind Snug & Outdoor describe themselves as a “team of artists” who aim to augment schoolyards and public land by reclaiming underused spaces.

Bermuda Triangle, Blue Whale, Brumleby

A crashed plane, the belly of a whale and topsy-turvy houses conjure entire worlds. In these wood and metal spaces, playing becomes a form of storytelling: mounting rescue missions, balancing on wings, and trying not to fall into the sea (or sandbox).

Bermuda Triangle, Blue Whale, Brumleby

The characters on Lost probably didn’t have so much fun clambering around their crashed plane.

Bermuda Triangle, Blue Whale, Brumleby

Inside the wood-slatted belly of a whale.