Darwin’s theory of natural selection illustrates perfectly what evolution is all about, the survival of the fittest if you will. It’s because of natural selection that a crocodile has an armor-like skin to protect it against enemies, a chameleon can change its color and camouflage itself for protection and hunting or humans evolved a more potent brain, and brought us to the forefront of evolution on Earth. It’s pretty well understood how evolution works, but the mechanisms behind it not so well, how a new feature or treat appears across an entire species, and so on.

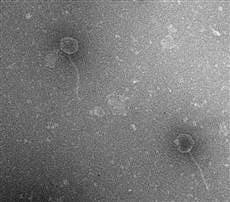

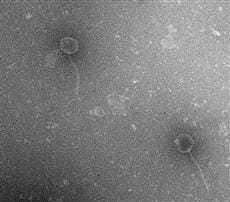

New research by scientists at Michigan State University has followed a virus called “Lambda” that mutated extremely quickly and developed the ability to infest a bacteria through a new doorway. Normally, the Lambda virus is inherently capable of infesting E. coli cells through a receptor LamB, on the bacterium’s outer membrane. When cultured under certain conditions, however, the E. coli cells develop a natural resistance to the LamB virus, and no longer produce the LamB receptors.

In 25 of the 102 trials, the virus acquired the ability to infect bacteria through another receptor, called OmpF. The researchers looked at the genetic changes associated with this new ability and found that all the strains that could infect the bacteria shared at least four changes. The other 80 viruses that attempted to infect the bacteria also mutated, but the researchers found that all four mutations had to be shared as a sum and work together to enter the host.

“When you have three of the four mutations, the virus is still unable to infect (the E. coli),” Justin Meyer, the lead researcher and a graduate student at Michigan State University, said. “When you have four of four, they all interact with each other. … In this case, the sum is much more than its component parts.”

Interestingly enough, a few months ago scientists in the United States and the Netherlands produced a deadly version of the bird flu, a virus which currently is just five mutations away from becoming transmissible to humans. It’s highly unlikely, scientists believe, for bird flu to naturally acquire all the necessary mutations for human infestation all at once. However, if conditions are favorable step by step, the virus might eventually evolve sequentially.

Meyer’s “Lambda” research implies that adaptation by natural selection, or survival of the fittest, plays an important role in the evolution of a virus.

“In other words, natural selection promoted the virus’ evolution because the mutations helped them use both their old and new attacks,” Meyer explained. ”The finding raises questions of whether the five bird flu mutations may also have multiple functions, and could they evolve naturally?”