They didn’t actually use other mastodons as killer pets, instead it’s been found that early hunters used mastodon bones for making deadly sharp spear heads. One interesting consequence to this is that Mastodon game season seems to have opened 800 years earlier than previously thought, offering a possible explanation for the blitzkrieg mass extinction of the species.

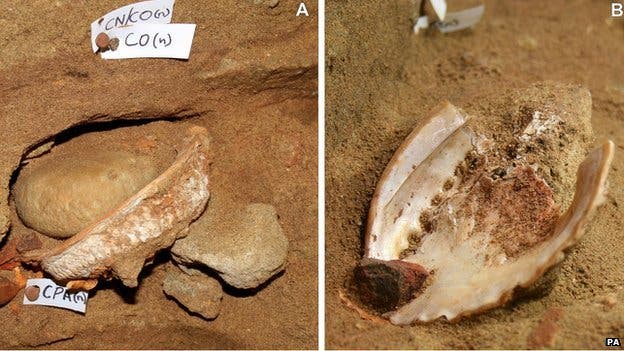

In 1977, Emanuel Manis, a farmer, found mastodon fragments, after which he went on to contact an archeologist. Carl Gustafson replied to his call and went on site to analyze the mastodon fossils, which turned out to be an almost complete skeleton. What struck his notice, however, was a sharp object embedded into the animal’s rib cage, which did not look locally native. Upon a further analysis, using a simple X-ray, Gustafson concluded that the object was indeed a mastodon fragment, only that it wasn’t part of the mastodon’s in question inherent skeleton. The best explanation he could find for the discovery for a foreign mastodon sharp bone was that it was actually the tip of a spear, launched by an ancient human hunter. Basically, mastodon’s were killed with

His hypothesis did not go unnoticed, and enticed the archeological community into a whole polemic around the matter. Many scientists contested his claim that the bone was sharpened into a man-made tool, as well as his dating. Gustafson dated it as being 14,000 years old, which would make it solid evidence for a much earlier mastodon hunting.

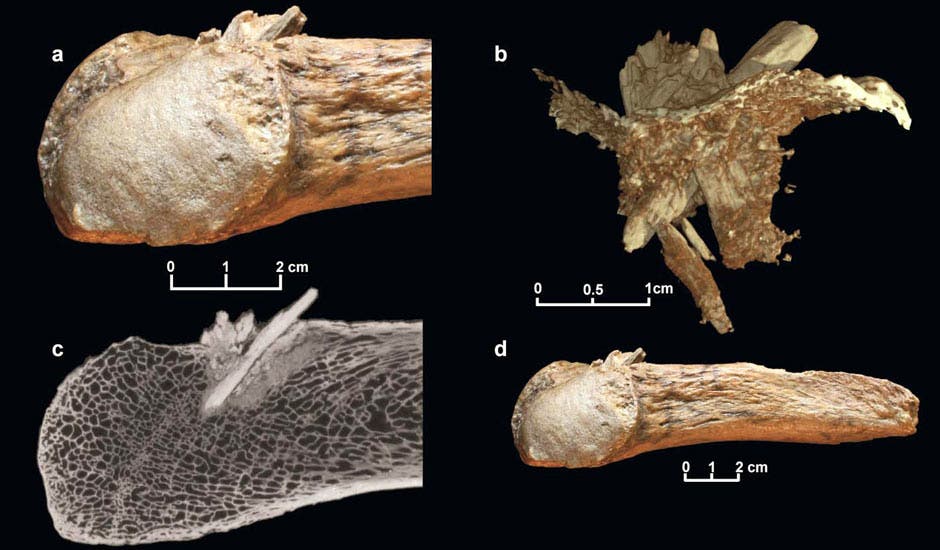

Professor Michael Waters of Texas A&M University revised the controversy decades later, still fascinated by the find. He wanted to settle this once and for all, so he contacted Gustafson about re-examining the specimen using modern technology. Waters eventually managed to bring the mastodon skeleton to the industrial-grade CT scanner at the University of Texas.

“It’s more powerful than a hospital one. They’re taking slices every 0.06mm, half the thickness of a piece of paper,” he says. “The 3D rendering clearly showed that the object was sharpened to a tip. It was clearly the end of a bone projectile point.”

He then went on to date the fragments, using a much more precise, modern technique than the one used in the 70s. His analysis showed that the mastodon was 13,800 years old, very close to Gustafson’s initial estimation. Then DNA analysis of the supposed mastodon spear head and a rib bone from the mastodon, showed that both came from the same species. Other sites found in the Wisconsin area also shows evidence of Mastodon hunting from 14,200 to 14,800 years ago, which would directly mean that man used to hunt mastodon in pre-Clovis time. The Clovis culture is considered to be the first established human presence in North America.

Despite all these data, however, other archeologists are still not convinced.

“It’s not definitely proven that it is a projectile point,” said Prof Gary Haynes from the University of Nevada, Reno. “Elephants today push each other all the time and break each other’s ribs so it could be a bone splinter that the animal just rolled on.”.

Waters has an answer to skeptical replies such as the one above.

“Ludicrous what-if stories are being made up to explain something people don’t want to believe,” he said. “We took the specimen to a bone pathologist, showed him the CT scans, and asked if there was any way it could be an internal injury. He said absolutely not.”

“If you break a bone, a splinter isn’t going to magically rotate its way through a muscle and inject itself into your rib bone. Something needed to come at this thing with a lot of force to get it into the rib.”

For the mastodon bone spear head to be effective, it would’ve had to puncture through hair, skin and up to 30 centimetres of mastodon muscle. “A bone projectile point is a really lethal weapon,” says Waters. “It’s sharpened to a needle point and little greater than the diameter of a pencil. It’s like a bullet. It’s designed to get deep into the elephant and hit a vital organ.” He adds, “I’ve seen these thrown through old cars.”

Michael Waters’ analysis was published on Thursday in the journal Science.

via ItsGOV