For most of us, many of the actions we undertake are made while taking into account how others perceive them. Sociologists call it the “theory of the mind”, and it’s the innate ability we have developed, as social beings, to form a personal social reputation – basically, we care what other think of us and our actions. Autistic individuals, however, don’t have this ability so well developed, as researchers have observed and studied in a recently published paper in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

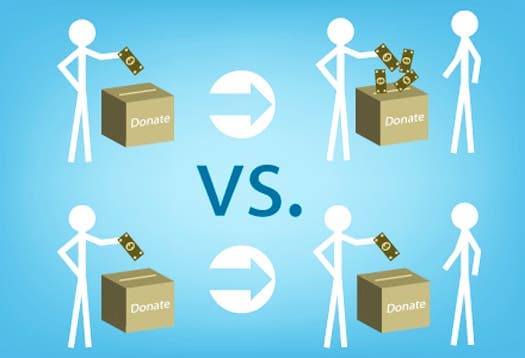

The researchers conducted a study in which participants were both people with and without autism. Each of the participants were asked to donate a sum of money to UNICEF, in two phases. In the first they had to donate a sum of money of their choosing when no one was looking at what they were doing, while in the second they had someone “looking over their shoulder”. When they were watched, people donated more due to social considerations, while autistic participants donated the same amount.

“What we found in control participants—people without autism—basically replicated prior work. People donated more when they were being watched by another person, presumably to improve their social reputation,” says Keise Izuma, a postdoctoral scholar at California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and first author of the study.

“By contrast, participants with autism gave the same amount of money regardless of whether they were being watched or not. The effect was extremely clear.”

Alright, but were the autistic participants truly careless of their social reputation of simply ignorant of the presence of other people watching while they were donating the sum of money? To assess this highly important parameter, the researcher asked the both types of participants, with and without autism, to solve a simple math test – first alone, then in the presence of another. Both sides performed better while being watched.

RELATED: Researcher unveils increase rate of autism

“This check was important,” says Ralph Adolphs, professor of psychology and neuroscience and professor of biology at Caltech and the principal investigator on the paper, “because it showed us that in people with autism, the presence of another person is indeed registered, and can have general arousal effects.

“It tells us that what is missing is the specific step of thinking about what another person thinks about us. This is something most of us do all the time—sometimes obsessively so—but seems to be completely lacking in individuals with autism.”

This can be both good and bad. For one, autistic individuals tend to be more sincere, as they they are indifferent of other people’s opinions about them. Of course, there’s also the social awkwardness involved, which is kinda of a bad thing for autistic individuals who can’t integrate in a social environment.

The study contributes to the ongoing analysis of this condition, helping paint a more vivid picture, not only for diagnosis purposes, but maybe more importantly to inform the general public. The second phase of the study will commence in the short future, as researchers are planning to MRI scan participants in order to understand at a brain activity level what goes inside an autistic person’s head while making these kind of social interactions.