Ever since uranium has been mined and atomic bombs have been tested, some areas have had to deal with the contamination of sediments and groundwaters by toxic soluble uranium. Now, this problem could be solved with filaments growing from a specific bacteria.

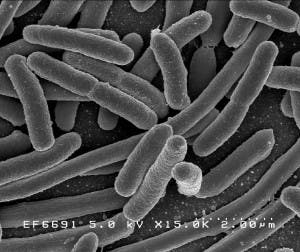

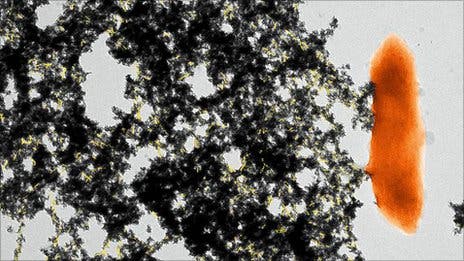

Some clean-up methods already use the bacteria to solidify Uranium in sediments, but the whole phenomena is not yet well understood, and as a result, cleaning up this radioactive element is extremely problematic. However, a team of researchers from Michigan State University has identified a group of bacteria known as Geobacter, which produces tiny protein filaments, or nano-wires, that remove the dissolved uranium from waters and precipitate it outside the cell. Their research explained how the whole phenomena works, and how it can be used to our advantage.

Practically, the filaments transform the soluble form of uranium into a less-soluble form which is much more easy to remove from sediments. The reaction is interestingly enough a by-product of the bacteria’s own metabolism, which generates energy by altering the chemistry other metals.

The team has found a way to purify the nano-wires in the natural population of Geobacter, and to genetically increase their concentration. They claim that “envisions these nano-wires being incorporated into devices, for use in places like Chernobyl and Fukushima where the radiation is too high for the bacteria to survive.”.

Such a filament measures only four nanometers across, but many of them create a network several times bigger than the cell itself, and the amount of solid uranium deposited is proportional to the number of filaments.

Via BBC