“This is the first study that has looked at how long those people can plan to live,” study author Edward Mills told Shots. “And we’ve found very, very positive results.”

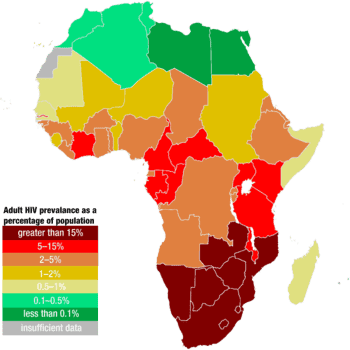

Indeed, a study conducted shows that over 22,000 infected people from Uganda that are receiving HIV treatment have about the same life expectancy as their countrymen who aren’t infected. The life expectancy of an average Ugandan is about 55 years. However, this is even better than the most optimistic prognosis ten years ago, when the first antiviral cocktails were first applied there.

“No one really foresaw how effective these drugs would be, and how many people could be treated late in infection and still have their immune function largely restored,” says Dr. Deborah Cotton of Boston University School of Medicine, who was not involved in the research. “We knew it was good. It turns out to be great.”

But this is not the end of the road, as things can get even better, if the infection is detected and treated earlier. The major issue however is that not everybody is receiving the treatment. Around 25 percent of Ugandan men are receiving treatment, when that number should be at around 40 percent, judging by how many are getting tested positive. The study seems to indicate that “men are ashamed about what they may or may not have done, and are not accessing care,” he says. “They may go to traditional healers or try to self-treat with aspirin. Or they reject the diagnosis of HIV”, which is never a good thing.

As a result, men go into treatment much later, drop out, or don’t go at all. Adolescents are yet another troubled group. They have the same death rate as the oldest Ugandans on the test group, which seems to imply that they were infected at birth and went their whole childhood without being treated, or even knowing that they are infected; a dire situation. However, Cotton believes that this kind of studies will bring new energies and efforts from the global AIDS community in its drive to get more people into treatment in developing countries, despite the insufficient funding.

“I think this will be a shot in the arm,” she says. “This has always been a motivated group of people – both patients and providers. But I think for many of us who’ve spent our lives working in HIV, we’re very committed to seeing the end of this disease in our lifetime. And some of us are getting older.”