Plants are able to remember information and react to it, thanks to an internal communications system that can be likened to a central nervous system in animals, according to a new study by a Polish plant biologist.

Plants “remember” information about light, and a certain type of cell transmits that information, much like nerves do in animals.

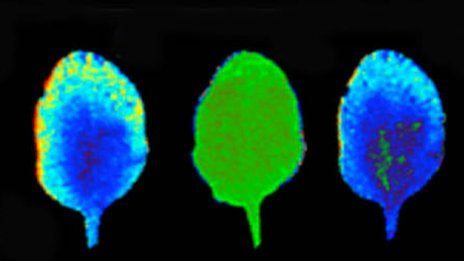

In the study, which was published in the early online version of the journal Plant Cell July 16, the researchers found that light shone on one leaf of an Arabidopsis thaliana plant caused the whole plant to respond. The response lasted even after the light source was taken away, suggesting the plant remembered the light input.

“The signaling continiues after the light is off; it is building short-term memory,” said the lead author, Stanislaw Karpinski, in an e-mail message. “The leaves are able to physiologically ‘memorize’ different excess light episodes and use this stored information, for example, for improving their acclimation and immune defenses.”

The leaves remember light quality as well as quantity, Karpinski added — different wavelengths of light produce a different response, suggesting the plants use the information to generate protective chemical reactions like pathogen defense or food production.

As reported by the BBC July 14, scientists found that light shining on a leaf cell triggered a cascade of events that was immediately signaled to the rest of the plant via a type of cell called a bundle sheath cell. Those cells exist in every part of a plant. Karpinski, of the Warsaw University of Life Sciences in Poland, measured the electrical signals from those cells, and compared it to finding a central nervous system for plants.

Terence Murphy, a plant biology professor at the University of California-Davis who was not involved in the research, said shining light on that first leaf could have any number of effects.

“The leaf would be loaded up with starch, maybe; that’s going to have a real effect on how it communicates through the phloem (vascular system) to other leaves. It’s not unreasonable that you could illuminate one leaf and affect the other leaves,” he said.

The trick is finding out how the other leaves are informed — and that’s what appears to have been done in the Polish study. Bundle sheath cells surround the veins in leaves, stems and roots, so it’s reasonable to think they transmit the electrical impulse, Murphy said.

Biologists have long known that plants can remember — they need to know whether they’ve gone through a cold season before they can germinate in the spring, for instance. It’s not memory as we know it, but a prolonged change in plant internal systems that causes effects later.

What’s more, scientists already know plants transmit electrical signals in response to a stimulus, just as nerves do. This is easily measured using a basic electrode setup, according to Murphy.

Karpinski said the light memory represents a new way for plants to respond to pathogens or disease — normally, they respond by direct contact with an invader.

“This information would not be a revelation untill we find that plant leaves can remember it for several days and process this memorized information to (bolster) their defense mechanisms against seasonal diseases,” he wrote.

Karpinski is well-known among plant biologists for earlier work on how plants respond to light stress. In a previous study, he also showed chemical signals can be passed throughout whole plants, allowing them to respond to and survive environmental changes. Understanding the mechanisms that cause those signals is a new step, however.

William John Lucas, distinguished professor of plant biology at UC-Davis and chair of the plant biology department, said an internal communication system would provide a wealth of information to different parts of the plant.

“A particular tissue within a plant needs to be able to signal to the rest of the plant in terms of what are its conditions, what should you expect,” he said. “If a young leaf is emerging out of a plant, it would be nice for that leaf to know about the conditions in which it is going to emerge.”

Lucas studies how plants pick up non-biological information, such as water and light, and how they transmit that information so the entire plant knows under which constraints it will grow. Plants can’t move to a sunnier, wetter spot, so they need to make the most of their environment.

Tapping into their “nervous system” would help scientists understand how they do that, Lucas said. That knowledge could lead to optimized food crops or hardier trees.

“There are no neurons in plants, but there is a communication network that we don’t fully understand,” he said. “There are important implications for these kinds of studies.”