After a breathless race through the ’80s and ’90s, desktop computer clock speeds have spent the last decade languishing around the 3 gigahertz mark. That stagnation in processing speeds has prompted scientists to debate whether it’s time to move beyond semiconductors — and what better place to debate than in the journal Science? Ars Technica gives a top-down overview of several future paths laid out in the journal’s latest issue by researchers such as Thomas Theis and Paul Solomon of IBM.

The main issue comes from voltages being forced to scale down as ever-tinier transistors are developed. That can lead to heat and power use problems, as well as slower switching and clock speeds. Chips have typically compensated by favoring size and power over speed, but scientists suggest several possible new approaches.

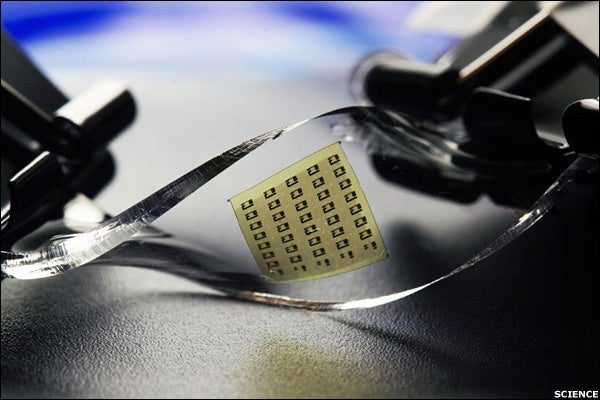

Some argue that clock speed is overrated, and that most interesting future innovations will come from smaller, flexible electronics built into smartphones, medical implants or even Star Trek-style clothing. Silicon ribbons can already do this to some extent, as long as people can live with their lesser power compared to a typical multi-layer silicon microchip. Extremely simple and small chips could also do the trick without requiring serious reengineering.

The IBM researchers tout the idea of finding a new transistor switch that can amplify small voltage changes. One promising approach which could achieve that goal is “interband tunnel FET,” which allows small voltage changes to maintain the necessary on-and-off states. But it only works with carbon nanotubes as opposed to silicon. Another approach would add a device that gives even small voltages an all-or-nothing impact — something that should allow for switching in less than a picosecond (one trillionth of a second), but in reality takes 70 to 90 picoseconds.

The last two ideas would move away from the old reliable silicon for semiconductors, and instead look toward transition metal oxide that combine oxygen with materials such as titanium and the rare earth element lanthanum. But there are so many transition metals and oxide combinations that researchers need a better way to predict the effect of any combos, lest they engage on a wild goose chase. We’ve also looked previously at studies aimed at using carbon-based graphene as a silicon replacement.

Material challenges aside, there’s reason for optimism. Silicon Valley hasn’t done too badly historically when it comes to cultivating a culture for innovation, and even the Pentagon’s DARPA has singled out the semiconductor industry as a model for others.

[via Ars Technica]