Researchers have already separated this group into two significantly different parts for a long time now: the primitive long-tailed forms and their more evolved, advanced short tail pterosaurs, some of which could reach amazing sizes. However, the gap between these two groups was so large that it seemed it could never be filled – until now.

In a study published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, scientists described a newly found animal that fits exactly in the middle of that gap;the pterosaur was named Christened Darwinopterus, as an homage to the 200th anniversary of Charles Darwin’s birth and the 150th celebration of his publication that changed the world, On the origin of species.

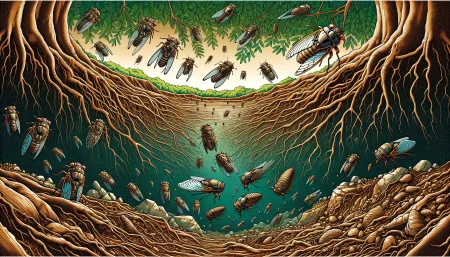

Gaps in fossil records are really not that uncommon, because only a smart part of the animals that lived becomes fossilized, and a small part of that small part gets found by researchers. Our understanding of those animals, as a result is seriously impaired. Such was the case with the pterosaurs. However, more than 20 skeletons of Darwinopterus (some of them complete) were found earlier this week in North-Eastern China in rocks that were dated to approximately 160 million years old. It had rows of sharp teeth, a flexible neck and long jaws, all of which suggest that this animal (who was about as big as a crow) hunted other contemporary flying animals.

“Darwinopterus came as quite a shock to us” explained David Unwin part of the research team and based at the University of Leicester’s School of Museum Studies. “We had always expected a gap-filler with typically intermediate features such as a moderately elongate tail – neither long nor short – but the strange thing about Darwinopterus is that it has a head and neck just like that of advanced pterosaurs, while the rest of the skeleton, including a very long tail, is identical to that of primitive forms”.

Dr Unwin added: “The geological age of Darwinopterus and bizarre combination of advanced and primitive features reveal a great deal about the evolution of advanced pterosaurs from their primitive ancestors. First, it was quick, with lots of big changes concentrated into a short period of time. Second, whole groups of features (termed modules by the researchers) that form important structures such as the skull, the neck, or the tail, seem to have evolved together. But, as Darwinopterus shows, not all these modules changed at the same time. The head and neck evolved first, followed later by the body, tail, wings and legs. It seems that natural selection was acting on and changing entire modules and not, as would normally be expected, just on single features such as the shape of the snout, or the form of a tooth. This supports the controversial idea of a relatively rapid “modular” form of evolution.

However, this research doesn’t actually solve a problem, it just shows that it can be solved. In order to fill all the steps that need to be filled, researchers have a lot of work ahead of them. However, the importance of this should in no case be underestimated, because if solved, it wouldn’t only show how it works, but also how massive rapid evolution took place on a large scale.

Dr Unwin concludes

: “Frustratingly, these events, which are responsible for much of the variety of life that we see all around us, are only rarely recorded by fossils. Darwin was acutely aware of this, as he noted in the Origin of species, and hoped that one day fossils would help to fill these gaps. Darwinopterus is a small but important step in that direction.”